By nature, endurance sports such as cycling and triathlon involve prolonged repetitive movement that can expose the body to small loads that accumulate over many repetitions to a relatively high amount of stress. When the cumulative stress is higher than the body is prepared to endure, the result is overuse injury. Whether you are training for an upcoming season of road races, an Ironman triathlon, a Gran Fondo, or your next Cycling House Camp, one of the main keys to successful training is maintaining a healthy body so you can put in the volume needed and desired in order to achieve your goals.

I am a physical therapist who specializes in treatment of endurance athletes with overuse injuries. I am also someone who has struggled with many injuries through my athletic endeavors that have been demoralizing but also avoidable. It has become my passion to share the knowledge that I have gained from both professional development and personal experience. This article will not be as simple as a list of “The Top 5 Exercises to Prevent Overuse Injuries in the Endurance Athlete.” While I have some personal favorites and certain exercises that I recommend more often than others, it is important that exercise recommendation is specific to the person, the sport, the point in the training cycle or season, and any injury history. Although a bit more abstract, my number one tip for injury prevention in the endurance athlete is: training load management strategies.

What exactly is an “overuse injury?”

Generally, the types of injuries sustained by endurance athletes are due to the small, repetitive loads placed on the joints, tendons, muscles, and ligaments. All of these tissues can only tolerate as much load as they are conditioned to withstand until they begin to break down from the demands of the activity in the form of what we call an injury. When the training loads are adequately and chronically higher than the body tissue capacity, we start to see injuries. However, one of the key principles of training is progressive overload: In order for a muscle to grow, strength to be gained, performance to increase, or for any similar improvement to occur, the human body must be forced to adapt to loads that are above and beyond what it has previously experienced. But how much load is enough to stimulate a change, and how much load is too much to increase risk of injury?

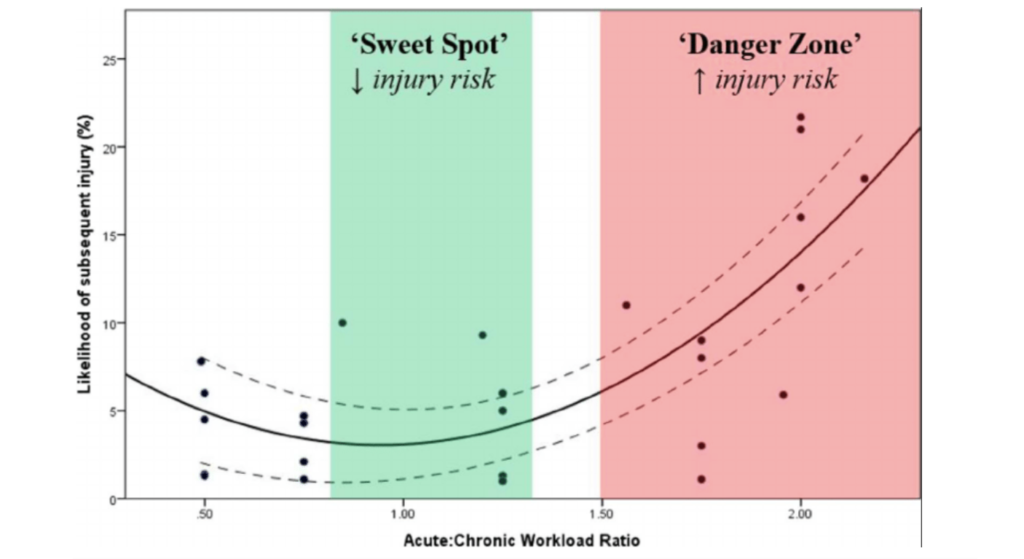

A substantial amount of research has tested the relationship between training load and injury. An effective load monitoring protocol can be very useful in the planning of training periodization to optimize physical condition while avoiding injury. Many folks use some form of training log for tracking distance ridden/run, average speeds, average and total power output, how they felt, etc. Some have coaches guiding the training periodization, and some prefer to “go by feel” or self-coach. One method for guiding training-load builds and tapers that has been studied and is becoming more and more popular is the Acute: Chronic Workload Ratio (ACWR). This is essentially a comparison of the size of the current week training load (acute load) to the average training load over the previous 3-4 weeks (chronic load). In order to determine current training ACWR, one would take the current week training load total divided by the average over the past 4 weeks. (The only rule is that the units of measurement must be the same. We will discuss options for this in the next section.) Values greater than 1 indicate that your load for the current week of training is greater than the average of what you have been doing on a weekly basis. Values less than 1 indicate less training load than the average of the past 4 weeks. What studies have shown, is that injury risk increases when your ACWR is > 1.5, indicating a relative spike in training load. An ACWR that is < .8 would indicate that the body is in a rested state. This may be a great place to be prior to a goal race, but if you are continually at <.8 week after week, your body is becoming de-conditioned for any future spikes in training load. However, when ACWR is between .8 and 1.3, studies have shown that injury risk is relatively low.

How do you best quantify “load”?

Most folks are accustomed to using measures of “external training loads.” This is essentially any metric that quantifies the work completed by the athlete. For example, for a cyclist it could be distance, time, or power output during a given training session. However, external training loads do not account for the individual physiological and psychological responses to external loads, combined with daily life stressors and other environmental and biological factors. These are called internal loads and can be quantified with measures such as rating of perceived exertion (RPE) or heart-rate. Stressors such as lack of sleep, poor nutrition, and stress from daily life can definitely impact performance and recovery and should be factored into training load management. For example, say you perform a hill workout on a familiar local climb. Two weeks ago, you were able to average 300W consistently for 5 hill repeats and you came away from the workout feeling tired, but able to ride hard again the following day on your local group ride. Two weeks later, you perform the same workout but after a stressful day at work where you didn’t have a chance to eat lunch and you slept poorly for the previous 2 nights. You were able to replicate the workout, but were barely able to reach the 300W average and came away from the workout completely haggard. The following day, you are sluggish and get dropped early on the group ride. This state is often indicative of a need for additional recovery, however, since you were able to log the same external training loads as the previous time, the overall added fatigue is not factored in. In order to objectively account for these factors that can inhibit recovery, I recommend tracking both internal and external loads. However, simply tracking total time of training session with or without average power can be adequate.

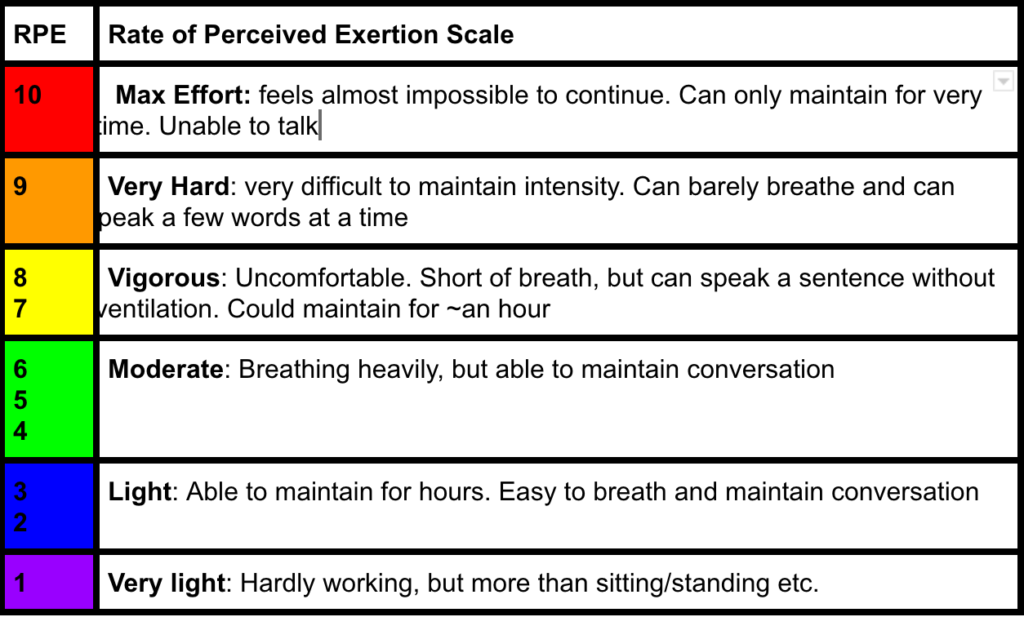

A common and very simple method for calculating workload that accounts for both internal and external loads and can be used for any sport (cycling, running, swimming, curling, ping-pong, etc.) is: Multiply the duration of the session by your RPE (I recommend using a scale of 1-10. See image below). For example, say you go for a 60 minute, easy-moderate spin. The session load would be 60(min) x 4(RPE) = 240. Say you are a triathlete and you follow the ride with a 30 min brick run with RPE of 7, the load for the run would be 30(min) x 7(RPE)= 210. Your total load for the day would then be 450.

Not only does this method allow you to account for internal and external training loads, but it also allows you to normalize loads across different types of sports. We all know that 20 miles of riding along a bike path, drafting behind your buddies will be much less load than the solo 20 mile ride up Mt. Lemmon (over 5,500ft of climbing).

If you’re not a numbers person and your eyes are glazing over, don’t worry! It’s not hard to track these numbers by using a spreadsheet that will auto-calculate your values so that all you have to plug in is your session duration and RPE. If you are interested in using such a spreadsheet, feel free to email me at endurancephysioanya@gmail.com. I would be happy to share the one I have created for myself and athletes that I work with.

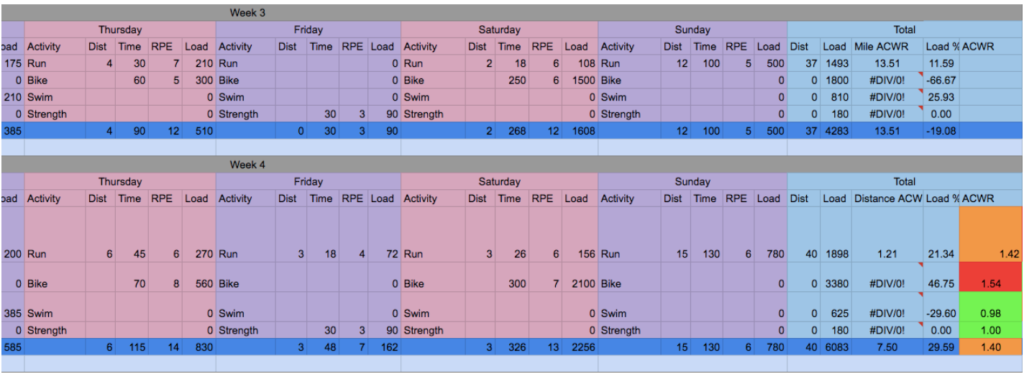

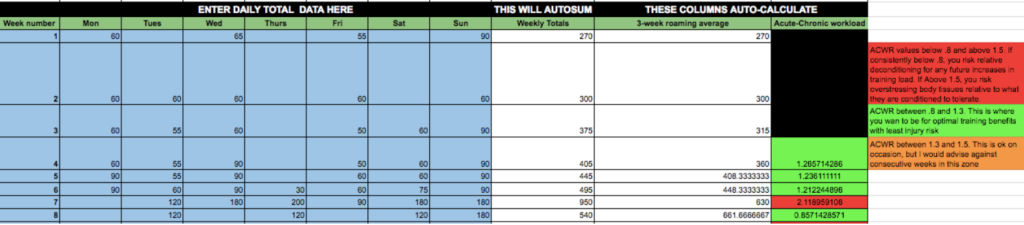

Below, I will outline some examples of how you can use the concept of ACWR to monitor your training loads. Make sure you really take a look at the images of the spreadsheets with the discussion below each image.

Example 1

In the above example, this triathlete has a relatively high ACWR for cycling >1.5, indicating a relatively large spike in cycling loads relative to what she had been performing. Her running loads are also increased although a little less compared to her chronic loads over the previous weeks (ACWR of 1.4). Her swimming is slightly decreased this week and her strength is exactly the same as what she had been doing. Does this mean she is going to obtain an injury from increasing cycling loads to quickly? Not necessarily, but it is a bit of a warning sign that she may want to be cautious with successive weeks in this red and orange zone.

Example 2

The above example is another option for monitoring loads that is a little more simple. This individual is only monitoring time on the bike. You can see that he had a rather large increase in cycling loading during week 7. Does this mean he will become injured? Not necessarily, especially if he has been a cyclist for a long time. If he can recover well from this week, it may mean he is that much more resilient to training spikes in the near future. But again, this spike in training load does put him at a higher risk for overuse injury and by monitoring these loads in combination with how his body is feeling, he may be able to plan future training in a way that will help him avoid these injuries.

Take-Home Points

Even if you choose not to track your training as suggested, realize that in an endurance sport such as cycling, one of the best ways to prevent injury is to assure you are 1) building relatively high chronic training loads in order to condition your body for future higher training loads; and 2) avoid prolonged periods of low training loads, knowing that your body will be less likely to tolerate a spike in training without breaking down. So this winter, I recommend coming up with a plan to maintain some level of training with a gradual build into the higher volume that is likely to come during the spring and summer. If you choose to not ride at all over the winter, but jump on a bike come April and start logging 4-hour rides, your body may not tolerate the spike in training. Does this mean you can’t have an off-season? Of course not! Just realize that you must gradually work back into training in order to respect the limits of your energy availability and body tissues. If you see your ACWR jump up above 1.5, does it mean you will become injured? No! It does mean you are at a higher risk for obtaining an overuse injury, but it all depends on so many other factors such as your ability to recover (sleep, nutrition, low stress etc.) and your chronic loads over the past years (have you been a cyclist for years, or are you relatively new to it?).

If you are prepping for a Cycling House Trip this winter, make sure you have a general idea of the approximate training volume for the camp so you can enjoy the trip. Realize that you may surprise yourself with how much you are able to tolerate during the week due to the ideal recovery environment: low-stress, good food, comfortable beds. You can also see how the relatively higher volume week may provide a nice high-volume week to boost your overall chronic load tolerance for continuing training throughout the season. Also, realize you will likely enjoy the trip much more if you are not attempting to put in a week that tips your ACWR into the 2-4 range. The take-home here is that your body will tolerate spikes in training load when you have built up a relatively high chronic training load. Be mindful of the impact that the repetitive movements may have on your body and respect that it will acclimate to the stresses you place on it if you allow it the proper recovery.

Thanks for reading! Feel free to contact me with any questions or comments.

Anya Gue

Anya Gue, PT, DPT, OCS

Endurance Physio

endurancephysioanya@gmail.com

Sports and Orthopedic Physical Therapy